The Hechinger Report is a national nonprofit newsroom that reports on one topic: education. Sign up for our weekly newsletters to get stories like this delivered directly to your inbox.

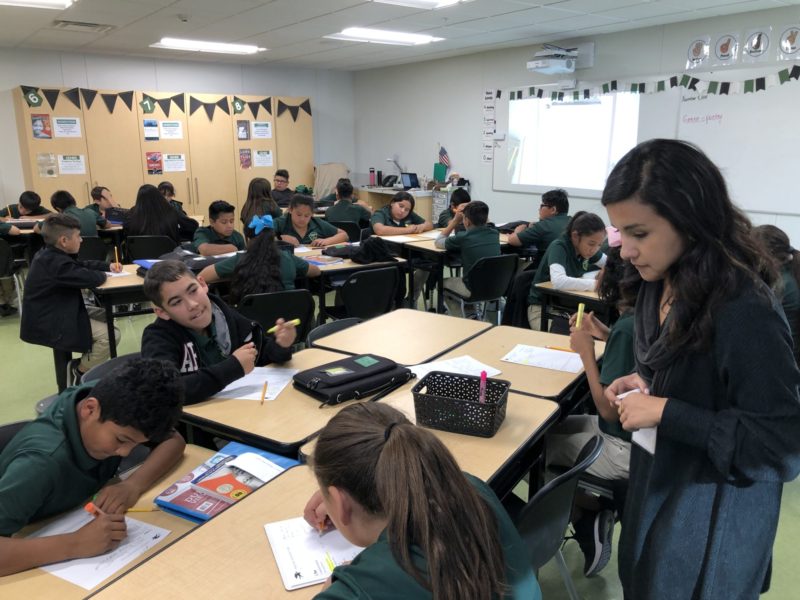

Groups of students at the Wonderful College Prep Academy in Lost Hills rotate for 1-on-1 time with the instructor. The practice is inspired by the Balanced Literacy approach to ELA.

LOST HILLS, Calif. — As a veil of morning fog slowly succumbs to the sun, Lost Hills emerges like a town that time forgot. Dust from nearby orchards sweeps by empty bus shelters, past a grove of uprooted almond trees stacked in heaps 20 feet high, and through a mobile home park where roosters guard abandoned cars and soot-covered trailers seem to admit defeat. The percentage of residents in this Central Valley town who boast a bachelor’s degree sits at 0. Farm work is a mainstay here, but it doesn’t provide much of a living: Farm workers earned an average of $17,500 in 2015, well below the federal poverty line of $25,750 for a family of four.

But on the town’s south side, the campus of the Wonderful College Prep Academy sparkles with a fresh coat of paint. A bright blue door opens to Acacia Briceño’s English class. They are reading the poem “I, Too” by Langston Hughes, and the time has come to dissect the third stanza, where the protagonist decides to stand up to bigotry.

“We are talking about racism, and they are incredibly engaged with that text. They start thinking about us, as Mexicans, and they start making those connections,” Briceño said later. “They have a really bad image of adults and teachers who have called them ‘stupid’ in the past. No one has ever really shown them how much they care.”

The business owners who employ many of the farmworkers here built the $29 million campus in 2017. The charter school, which serves kindergarten through eighth graders, is the second in a chain started by Lynda Resnick and her husband, Stewart. They own The Wonderful Company, the $4.6 billion conglomerate behind Fiji Water, PomWonderful pomegranate juice, and Teleflora, the country’s largest flower delivery service. The company is also the world’s biggest processors of almonds and pistachios.

“This is my legacy,” said Resnick from her office at Wonderful headquarters in West Los Angeles. Unhappy with the global but ill-defined reach of her charitable work, Resnick turned to place-based philanthropy and began to wonder what she could do for her Central Valley employees. “And of course, education is the most important thing. I want to change the paradigm of poverty in the Central Valley.”

With about 4,500 full-time employees in the area, The Wonderful Company is one of the region’s largest employers, and, while its full-time workers are paid more than the state’s $12 per hour minimum wage, many of its employees are just scraping by. Almost one third of the children in the county live below the poverty line. Until December 2018, Wonderful workers earned a minimum wage of $11 an hour. A year ago, the company raised its minimum wage to $15 per hour for full-time employees it hires directly.

Even as the company was raising pay for its full-time employees, 1,800 Wonderful workers launched a strike after a contractor for the company reduced bin rates for mandarin oranges from $53 to $48.

Wonderful Education, a division of The Wonderful Companies, runs the charters that serve children near the company’s two largest plants, a citrus plant in Delano and a pistachio plant in Lost Hills, where, company sources said, one of every two households holds someone employed by the company. About 35 percent of Wonderful’s students at Lost Hills, and 10 percent of its students in Delano, are the children of Wonderful employees. Nearly 99 percent of Lost Hills students, and 93.8 percent of Delano students, are Latino.

The Delano charter, which now hosts 1,800 K-12 students, opened in 2009.

Second and third graders at the Wonderful Hills College Prep Academy in Lost Hills line up for Morning Motivation, an opportunity for shout-outs, birthday celebrations and the Pledge of Allegiance.

College is a blurry dream for many of these families — hard to fathom, out of reach. Many students’ parents never finished high school. But, like many charter schools, the Wonderful Schools are fixated on college, with banners for the University of Florida and Harvard waving in the halls and classrooms, and a rigorous curriculum meant to prepare students to get there. “When opening the school, it was important for us to see what the leading charter schools were doing with similar demographics,” said Alesha Hixon, senior director at the Lost Hills charter.

What’s different about the Wonderful schools is that they also offer a second track for students. At the Delano branch of the charter network, the Wonderful Agriculture Career Prep program is a four-year college pathway, ending in an associate’s degree in an agricultural field. It was designed to fill the skills gap that The Wonderful Company faces as agriculture gravitates toward a more technologically advanced workforce.

Related: In a North Carolina county where few Latino parents have diplomas, their kids are aiming for college

After graduation, the company offers students a one-year work fellowship, with a guaranteed income of $35,000, slightly above the county’s average income. Students who don’t accept a fellowship can continue their education at a four-year college with the company’s help.

It’s unusual for a single company to take on running a school. Georgia Heyward, a research analyst at the Center on Reinventing Public Education, said when businesses do get involved in charter schools, it’s typically via collaborative efforts among several partners, not by designing and running a school itself.

“That’s always tricky, when you have a single entity that has an interest,” said Heyward. “It’s good practice in education to be including communities as much as possible, to ensure that you don’t have any one actor who is behaving in their own interest.”

(Wonderful school programs work with outside partners across the Central Valley, reaching nearly 117,000 students in 165 schools.)*

The Wonderful College Prep Academy’s $100 million campus in Delano, for 1,800 K-12 students. Photo: Alfonso Serrano for The Hechinger Report

C

ollege is central at The Wonderful Schools, but so are the farming and health food interests which are at the center of the business of its parent company. On a recent morning, several sixth graders leaned over planting beds that mark the center of campus. They were tweaking a drip irrigation system that nourishes beds of kale and broccoli.

Wonderful officials are engrossed in the school’s nutritional program. During the school’s next phase of expansion, they hope to add a learning farm, with the goal of growing enough produce to stock the school kitchen.

“We are a healthy food company,” said Resnick. “We walk the walk.”

Resnick said diabetes among Central Valley residents is a major concern. She said many children at the charters must go to medical visits with family members who, for example, receive dialysis three times a week, or who have had digits removed because of the disease. “It’s a scourge in the Central Valley,” said Resnick. “So, educating them at an early age, they will be healthier, they will be more fit, and they will understand why.”

In the meantime, chefs bustle in the cafeteria as they prep for the lunchtime rush. The school pushes whole grains and produce as much as possible. The kitchen offers a “vegetable of the day” twice a week. And wellness boosts to menu items are a common feature: almond milk with a dab of cinnamon, for example, or pomegranate juice spiked with apple cider vinegar. All meals are made from scratch.

The Wonderful Company’s healthy diet crusade, a central pillar of the schools’ educational focus, has not come without pushback. For students who’ve grown up eating Mexican-inspired meals rich in fat and sodium, a serving of kale with granola croutons may seem like a form of after-school detention.

“When we announced that so-and-so was coming in to talk to them about nutrition, they got so angry,” said Resnick. “They’re used to eating pan dulce for breakfast, and we’re serving a healthy breakfast every day. We’ve had broccoli thrown at us.”

The initial food fights, however, have gradually given way to consent. Early in the school year, chef Kelly Wangard tried serving a Caesar wrap. It was a flop because students mistook it for a cold tortilla. The following month she served chicken Parmesan in a whole grain tortilla, rolled up and served hot so that it looked like a taquito, with Caesar salad on the side. The students loved it.

“It’s crazy how it’s transitioned,” said Wangard. “They’re telling me what they want instead of me telling them what to have. So, it’s kinda cool to see those lifestyle changes. It’s completely foreign to them.”

To ease the cultural jolts that students encounter, the Lost Hills charter has sought to engage parents, many of whom have limited English. Part of that outreach includes a 10-week, school-based program for parents that covers nutrition, language development and family communication.

Maribel Vargas, a native of Mexico City, welcomes the cultural shift she sees in her daughter, a seventh grader. Raised to believe that schools always know what’s best, Vargas applauds her daughter’s healthy eating habits, even if they clash with her own.

“I don’t have that education to eat healthy because I don’t know how to cook that food,” said Vargas in Spanish. “If she adopts that here, I find it fantastic. Now my daughter asks if something is healthy when I cook at home before deciding to eat it.”

Jorge Ochoa’s job at Wonderful Schools is perhaps a bigger task than Wangard’s: to convince a generation of parents that college is not beyond the reach of their children. He must also persuade the students themselves. Some said they fear they’re not good enough for college or that their fate rests in the fields.

Ochoa grew up in the Central Valley, the son of farmworker parents who labored in the citrus orchards that surround Delano. After graduating from New York University with a master’s in education, he returned to Delano, where he is director of College Programming at the Wonderful College Prep Academy.

“The focus here is what we call ‘cradle to career,’” said Ochoa as he strolled through the sun-drenched Delano campus, a $100 million layout that replicates a typical college campus: a centrally located quad with adjacent lecture halls, student centers and a dining hall inspired by Google’s cafeteria in Mountain View. “We support our students from the beginning of elementary school in what it means to have families be college ready.”

He oversees a series of workshops targeting parents. One explores the ACT Test. Another delves into the FAFSA and what parents can do to help their children apply for federal financial aid. The efforts have paid off. The state recently recognized the Delano charter as among California high schools with the highest number of FAFSA completions, a nearly 100 percent rate.

Related: A free sandwich can make the difference for some migrant worker children in college

ELA teacher Acacia Briceño watches over her sixth grade class.

“College ready” at the Delano campus also means that, by the time they graduate, most students will have gone on roughly 20 college tours. Children of company employees who graduate with a 2.5 GPA or higher receive a four-year renewable college scholarship, $4,000 annually for California State schools and $6,000 for private schools or the University of California system — whether they attend one of the Wonderful charters or another area high school.

Eighty-two percent of graduates at the Delano charter go to a four-year college, and 70 percent of them finish their studies and earn a degree, eye-popping figures when compared to national rates for similar demographic groups. (The Lost Hills campus only enrolls middle schoolers so far, and hasn’t graduated a senior class.) The national rate of college completion among low-income students sits at 9 percent. Among children of parents who have not graduated from high school, a sector heavily represented at Delano, the completion rate is around 5 percent.

“Most parents are field workers — they did not go to college,” said Irelda Alarcón, a senior at Delano who credits the school with changing the mindset of students, many of whom feel they don’t have what it takes to reach higher education. “I live in a Mexican household. My parents did not go to college, so I’m the first person in my family to have the opportunity to take college courses.”

The school’s college success rates have come as something of a surprise to the company. When school administrators developed the agricultural studies program, they projected that about 50 percent of students would take on employment at Wonderful. Last year, however, 96 percent of students decided to bypass the company and attend a four-year college.

The Ag program’s coursework focuses on developing math and computer skills; by the time students graduate high school, they’ve earned an associate of science degree with a focus on Ag Business, Plant Science, or Ag Technology. The Wonderful Company partners with six other area high schools to provide the Ag Prep program, which reaches about 2,200 students in grades six through 12.

Company executives, including Resnick, insist they’re not discouraged by the high number of students sidestepping the company.

“The more they go to college, the happier I am,” said Resnick. “Yes, we can use the manpower, absolutely. But it’s really for the kids. I don’t have an ulterior motive. You can dig all day. You’ll never find one.”

“There are definitely some kids who need to get to work in the communities they come from,” said Noemi Donoso, executive vice president of Wonderful Education. For Donoso, the college attendance rate means the program is a huge success. “And as we talk to the [Wonderful] company executives, they’re like, ‘We’ll have a job for them with a college degree.’”

I

n a Harvard University-themed classroom, Jessenia Anaya and a few of her seventh grade classmates hovered over a plant submerged in a glass beaker. They were observing how the blooming plant produces oxygen.

Anaya herself has begun to blossom at the school. This spring she placed second in a statewide speech and debate tournament sponsored by the California Department of Education. “I’m good at arguing,” said Anaya with a vitality that left no doubt. “I want to be a lawyer.” She also wants to attend Harvard, a long distance from the trailer home in Lost Hills where she and her family live.

Anaya’s academic achievements may be exceptional, but her success is symbolic of the Lost Hills charter’s extensive progress in just two years. Before the school’s creation, during the 2016-17 academic year, just 15 percent of sixth graders in the local public school graduated proficient in English language arts, and 7 percent met or exceeded math standards.

By the end of Lost Hills’ first academic year, 65 percent of its sixth graders passed the state English exams and 38 percent passed math. Lost Hills expects three quarters of its sixth graders to meet standards by the end of eighth grade.

Resnick’s ambitions for her schools aren’t yet satisfied. The next phase of development in Delano launches in August, when the campus will expand to include a four-year teachers college. School administrators describe the recruitment of qualified teachers to the Central Valley as a constant obstacle, despite the housing subsidies and competitive salaries that Wonderful offers.

Wonderful’s high school students interested in sticking around and becoming teachers will be able to follow a teaching pathway through high school, and then enter college on the Wonderful campus to pursue bachelor’s and master’s degrees in education, while also working part-time at the company’s charter schools.

“The bane of our experience is finding good teachers,” said Resnick, describing plans for a teachers college. “So, it’s just a perfect idea. We have to grow our own. There is no other way.”

This story about the Wonderful College Prep Academy was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s newsletter.

*Clarification: This story has been updated with an addition noting that Wonderful Companies works with other entities in the region.