The beginning of autumn brings many milestones: crisp weather, changing leaves and jack-o’-lanterns. Much less welcome if you have an early-rising toddler, autumn also brings the end of daylight saving time, commonly known as “falling back,” when much of the Northern Hemisphere will set their clocks back one hour, returning to standard time. In the United States this year, daylight saving time will end at 2 a.m. on Sunday, Nov. 3, and will return in the spring, at 2 a.m. on Sunday, March 8, when the clocks “spring ahead” one hour.

Parents of small children often dread these shifts, which can upend nap and bedtime routines. But with an understanding of how the time change affects sleep, and a bit of planning, you can help ease the transition for your family.

[Learn how to move your child to a separate room.]

Why do we have daylight saving time anyway?

Daylight saving time was first observed in Germany in 1916, in an effort to reduce wartime energy costs by better synchronizing daytime activities with natural daylight hours. It was adopted universally in the United States following the passage of the Uniform Time Act of 1966; though states were allowed to opt out, only Arizona and Hawaii elected to do so. Today, about 70 countries observe daylight saving time during the summer months.

These shifts in schedule are analogous to an hour of jet lag. Though there’s a rule of thumb that it takes one day to adjust to one hour of jet lag, it can take longer, and side effects such as night wakings may occur with even modest time shifts

What are the consequences for kid and grown-up sleep?

Anxious parents often wonder how these time changes will affect their children’s sleep (and thus their own). There is little research on this topic in children. In general, small children (and their parents) will struggle more with falling back, while teenagers — or anyone who needs an alarm clock to wake up in the morning — will struggle with springing ahead.

“Falling back”

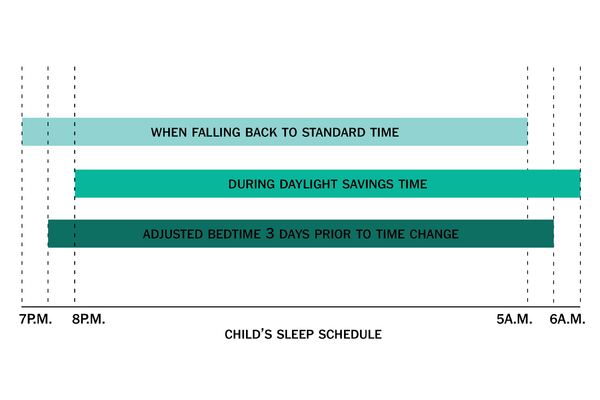

If you don’t have children or work nights (if you’re unlucky enough to be working the graveyard shift on Nov. 3, you’ll be on call for an extra hour), congratulations! You get an extra hour of sleep. For those of us with children who wake us up in the morning, however, falling back can be painful. Toddlers already tend to get up earlier than their parents might desire; with the time change, a child who typically sleeps from 8 p.m. to 6 a.m. will now be on a 7 p.m. to 5 a.m. schedule. The sleep period has not moved, but the clock has.

Some of the patients I see in my work as director of the Pediatric Sleep Center at Yale-New Haven Hospital really struggle with this transition. Although there is little research on the topic, I find that children who have developmental problems such as autism may especially suffer. Likewise, if you are already working on a sleep issue with your child, you may encounter extra difficulty for a week or two.

Fortunately, this is pretty easy to address. Move your child’s bedtime later by 30 minutes for three days before “falling back,” and then return to his old schedule after the time change. For example, if your child normally sleeps from 8 p.m. to 6 a.m. encourage him to sleep from 8:30 p.m. to 6:30 a.m. for three days before falling back, then return to the old 8 p.m. to 6 a.m. schedule on the new time.

Not everyone’s child will sleep an extra 30 minutes, but the important thing is to move bedtime. This approach can help cushion the landing from “falling back” so you get a little more shut-eye yourself. You can also help yourself by actually sticking to your normal bedtime on the first night after falling back, even though your body may feel like it’s an hour earlier.

Unlike little kids, teenagers naturally tend to stay up later and struggle to get up in the morning. Thus, “falling back” tends to feel pretty great for your teenager as the world essentially moves one hour closer to his or her natural sleep schedule. If you want to capitalize on this, I encourage teens not to use the new clock time as an excuse to sleep in or to stay up later on the day after the change. Practically speaking, this means continuing to go to bed a bit earlier based on clock time. For example, if your teen struggles to fall asleep before 11:30 p.m. on Sunday nights, this is a good opportunity to have her go to sleep at 10:30 p.m. This new clock time will feel like her old bedtime, but get her more in sync with her school schedule.

“Springing ahead”

The beginning of daylight saving time is going to be hard on anyone who struggles to get out of bed in the morning, due to the loss of an hour of sleep. If you need an alarm clock to wake up in the morning already, this one is painful.

For teenagers, it is especially difficult to make this adjustment. First, an hour of sleep is lost. Second, and even more important, this entails shifting the sleep period one hour earlier; it is always easier to stay up a little bit later than to go to bed earlier as our natural body clock operates on a day slightly longer than 24 hours.

If you have younger kids who rise early, “springing ahead” can be a net positive in that their apparent wake time will be an hour later. So, if your child typically gets up at 5:30 a.m. and you are not happy about it, just wait until after the clocks “spring ahead” and she begins magically getting up at 6:30 a.m. Of course, she may also be going to bed at a later clock time as well.

The take-home

The beginning and end of daylight saving time can cause sleep problems for parents and children alike. Younger children will get up earlier after falling back and teenagers will struggle after “springing forward.” Tired parents will lose either way. Making some modest changes to your child’s sleep schedule beforehand can help cushion the blow.

[Read Craig Canapari’s advice on getting your kids to sleep in the same room.]

Craig Canapari, M.D., is an assistant professor of pediatrics at Yale University, director of the Pediatric Sleep Center at Yale-New Haven Hospital and the author of “It’s Never Too Late to Sleep Train.” He blogs about childhood sleep issues on his website.