This is part one of a 10-part Oregonian/OregonLive series on youth mental health. Return to OregonLive throughout the week for more stories on the topic.

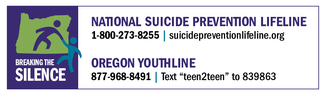

Portland teen Sheherazade Weyland, 18, answers young people’s crisis calls and texts at a crisis hotline for children and teens. Calls to the Oregon YouthLine range in severity from distress about a thwarted crush to a young person actively considering suicide. And Weyland and other volunteers at the YouthLine see a clear trend: Among young people, mental health issues are revealing themselves more often and at younger ages.

Weyland noted that callers age 10 to 12 often reach out because they’re contemplating suicide.

“It’s important to remember that an 11-year-old can be suicidal,” Weyland said. “People don’t want to acknowledge that because it’s horrifying. … We don’t want to look at a little kid and think they could hurt themselves.”

But young people can and do: Suicide is the second leading cause of death for young people ages 10 to 24 in Oregon. Between 2010 and 2017, almost one-fifth of deaths of Oregon children ages 10 to 14 were the result of suicide. And the suicide rate for those 10 to 24 increased steadily from 7 suicides per 100,000 in 2010 to 14 in 2017, according to Oregon Health Authority records.

National trends show a steady increase in suicide across all age groups. And Oregon’s suicide rate, both overall and for young people, has outstripped the national average for years. In addition to those deaths, hundreds of Oregon youth are hospitalized every year for self harm and suicide attempts. The state also has one of the highest rates of youth depression in the nation, according to non-profit advocacy group Mental Health America.

What’s causing so much distress?

Mental wellness is individualized. No one factor or discrete set of factors causes youth to feel like ending their lives.

But people in Oregon and around the nation with direct experience in youth mental health cite three high-level drivers behind the rise in young people hit by depression, anxiety and other mental health challenges: increased academic pressure, the rise of social media and existential fears stemming from school shootings, climate change and other horrors that have colored their childhoods.

Or, in simpler terms: “Kids are dealing with a hell of a lot more than when we were little,” said Kristi Dille, president of the Oregon Parent Teacher Association.

‘Achieve, achieve, achieve’

Academic stress causes serious mental anguish for many young people, kids, teachers and clinicians say. School is more challenging than it used to be. College looms over most students’ heads, whether they feel that’s the right option for them or not. Standardized testing can make or break a student’s perceived success. The system doesn’t flex, they say, for students who learn differently or those who want to chase dreams outside of a college degree.

Anne Gearity, a Minneapolis-based mental health clinician and professor at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities, has consulted with schools about students’ mental health for almost 30 years. She has noticed how the education system has become more stressful for students over time.

Gearity notes that the federal No Child Left Behind law, which vastly increased the frequency of standardized testing in schools nationwide, had the opposite effect of its name. In many cases, she said, “Tests became the only markers of success.” With such a narrow definition of accomplishment, kids who score below grade level but register gains toward that benchmark aren’t often acknowledged for their progress, she said. “We defeat [such students] before they even have a chance.”

In too many cases, Gearity and others in the education field say, the goal morphs from ensuring students are learning to polishing a school’s image with high test scores.

“If you get a perfect score on the SAT, but you’re suicidal, you’re not going to get far in life,” said Lindsay Ray, a math teacher at Beaverton’s Westview High. She says people outside the field of education underestimate how acute the need for mental health services is in schools and how the lack of that care prevents students from learning.

For students who make it through their K-12 years, getting into college and earning a degree has become the single marker of success, say young people facing those pressures.

Sophie Rupp, 19, also volunteers at Oregon YouthLine. She said she felt pressure from her peers not to take a gap year after high school, even though she felt that was best for her.

“There is so much pressure these days to just go to college,” she said. “I was so stressed out by that. My friends were like, ‘You shouldn’t take a gap year, you’re going to be so bored, what are you going to do with your life, why waste it?’”

As with any life decision, different paths work for different people at different times. Even Rupp, who was only delaying college not forsaking it, felt the pressure to conform to that one ideal of college attendance.

The Portland teen is glad she didn’t succumb to it. Taking a gap year “is the best thing I’ve ever done,” she said. “I had time to figure out who I am. I got to travel. I got to work at YouthLine more.”

Now that she’s had that time, she’s heading to Scotland in the fall to study psychology.

“I definitely think alternative routes should be pushed more at schools,” Rupp said.

Weyland, her fellow “YouthLiner,” had a similar experience. After attending a community college for two years, she transferred to a four-year school in Michigan to finish her degree in political science.

She hated it.

“My mental health deteriorated. I was spending every day in my dorm room, sad and alone, and it was horrible.”

Yet heading home was not easy.

“Choosing to leave and drop out was the most difficult decision of my life because there are so many societal pressures that you have to just get through it and you have to get your degree in a certain amount of time,” Weyland said. “It’s a lot of pressure and it’s pretty ridiculous we want people to prioritize that above their own mental health and wellness.”

Now, Weyland is enrolled in a dual enrollment program at Portland Community College and Portland State University to finish that degree. By the time she finishes, she’ll have spent six years working toward it. But that’s okay, she said. It’s necessary to normalize experiences that don’t conform to expectations, she said, because when that doesn’t happen, young people internalize stress and spend more time in situations that are unnecessarily stressful, as Weyland did.

“The pressure on these kids is so great to achieve, achieve, achieve,” Gearity said.

‘Is the world going to be here when I’m an adult?’

Climate-change crisis: Oregon faces wildfires, drought and deep economic losses

UCC mass shooting: Killer ‘angry at the world,’ mom told detectives

Oregon had the 6th biggest rise in reported hate crimes in the nation over a 4 year period, study says

America and its young people live in an age of near-constant bad news. OregonLive, like other news websites, is replete with headlines that stoke young people’s existential fears: stories highlighting climate change, mass shootings, political hate and the like.

Young people see them. And they’re scared.

“I remember when I started in the field, it seemed like a lot of the concerns were just about my universe, my little world, and now it’s a lot more,” said Galen Cohen, a school-based therapist at Madison High in Northeast Portland. Now, he said, he sees students with questions like: “Is the world going to be here when I’m an adult? What’s my role in that? What’s happening with this political system, especially if I don’t have a vote yet? What are the adults doing with my world?”

These concerns can manifest in mental health issues, including depression and anxiety, Cohen said.

Sophie Rupp tucked things that make her happy or that direct her thoughts in a healthy direction into the self care kit she keeps with her when volunteering at YouthLine. (Photo by Beth Nakamura/Staff)

Weyland says such fears aren’t just about the future; some are immediate. Older millennials who graduated into the post-recession world are sending bad vibes to the younger Gen Z generation.

“There’s this sense of impending doom from the generation before us,” Weyland said. The college debt crisis, underemployment and the inability to afford a mortgage or kids all loom, along with the resurgence of neo-Nazi groups and estimates that we have just 10 years to solve climate change before it’s too late.

There’s a sense of “What the hell am I doing? Everything is on fire,” Weyland said. And this sense of “impending doom” trickles down to those at the start of their adult lives.

“It’s hard to be excited for college when it’s like debt, debt, debt,” she said.

Young people also fear for their personal safety. Every month, it feels as if there’s another mass shooting in a place that felt safe the week before: schools, concerts, and now, garlic festivals. All three people killed at the latter gathering were younger than 20; one 6-year-old was injured by gunshots in a bouncy house.

Lori Shontz, professor of journalism at the University of Oregon, studies the impact of reporting on traumatic events like mass shootings.

When she teaches about covering these events, she often has students who have personal experience with mass shootings.

Shontz said that whenever she enters a classroom, she checks for an escape route. After all, an assistant English professor at Umpqua Community College and eight of his students died when a gunman targeted their class in a 2015 mass shooting. “If I’m 50 and I’m worried enough to do that,” Shontz said, “I can’t imagine what it’s like for students.”

‘Perplexed and confused and overwhelmed’

After a cluster of student suicides in Salem last year, Salem Health, the organization that runs the hospital in the city, partnered with the school district and other community stakeholders to host listening sessions about youth mental health at every Salem-Keizer high school.

One theme came up at all of them: social media.

“We are all feeling out of control and powerless when it comes to social media,” said Leilani Slama, vice president of community engagement for the Salem Health Foundation. “I think especially the adults feel that social media is significantly contributing to this problem but they don’t know how to change that … It was pretty obvious to me that parents and teachers feel very perplexed and confused and overwhelmed. They think it’s a bad thing, but they don’t really know how to frame it as a bad thing, and they don’t know how to make kids understand that it can make you feel worse.”

It’s an extremely common sentiment among parents, clinicians and others who interact with young people.

But the issue is more complicated than it appears on the surface, especially for youth in middle and high school, according to Nick Allen, director of the Center for Digital Mental Health at the University of Oregon.

Social media is not a problem in and of itself, even though conversations about it are often framed that way, Allen said. Social media “acts as an amplifier to what’s happening in your life offline,” he said, which means taking a teen’s phone away doesn’t address the problem.

“Social media is what you make of it,” Weyland said, who is 18 and also hears from many young people about social media. “People can have very unhealthy relationships with social media in the way they can have very unhealthy relationships with anything.”

Weyland gives the example of a person with a negative relationship with their body: If a young person struggles with body image and spends a lot of time scrolling through profiles of Instagram models, magnifying those negative ideas, the problem isn’t going to go away if social media is seen as the sole cause. The underlying cause still exists, Weyland said.

Many adults frame problems posed by social media as adolescents not knowing any better. Young people disagree.

“Most teenagers aren’t stupid, and if they’re having a problem with social media, they know that’s where it’s coming from,” Weyland said. “Maybe they’re struggling to get away from it, maybe they’re using it as a form of self harm, maybe they’re addicted, maybe there’s other things going on. But I guarantee you if you ask, ‘Is social media negatively impacting your mental health?’ they’d say ‘Yes.’ It’s not this unconscious thing that we’re so immersed in this online world we don’t recognize what it’s doing to us.”

That’s not to say people concerned about young people’s mental well-being should ignore the impact of social media on mental health. Many clinicians advocate for limits on social media usage, noting it can interfere with sleep patterns.

Cohen, the school-based therapist, said he sees students lose sleep in the name of social media because they’re afraid of losing social connections. “If I miss out on notifications in the middle of the night, my friend group might not be there in the morning” is the mentality, he said. Social media can amplify a teen’s worries about the strength of friendships, as well as other concerns, he said.

“Dismissing teen problems as just because of Instagram is one of the fastest ways to make sure a teen doesn’t talk to you about their problems,” Weyland said.

–Casey Chaffin; cchaffin@oregonian.com; @todaycaseysays