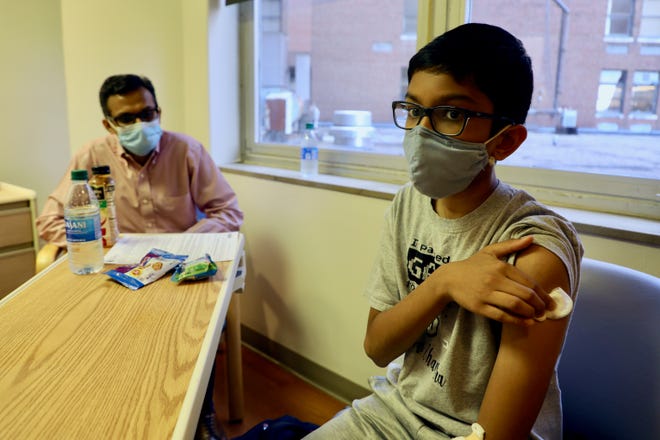

After school Thursday, 12-year-old Abhinav pushed up his T-shirt sleeve and looked down as a needle pierced his left shoulder.

The Ohio boy is one of the first children allowed to receive a vaccine designed to protect against COVID-19. His father, Sharat, also joined the trial.

After months of testing its COVID-19 candidate vaccine in adults, Pfizer recently lowered the age of participation to 16, aiming to include at least 3,000 older teens. On Thursday, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital inaugurated an even younger group, vaccinating its first two middle schoolers.

Pfizer is the only one of the leading drug companies to allow minors into a vaccine trial.

Some pediatric vaccine experts say drugmakers and federal regulators should wait until the vaccines have been proven safe and effective in adults before moving to children.

“If I were part of the FDA I would certainly want to be very convinced about the safety of a vaccine before I approved its use in children,” Dr. Cody Meissner a pediatric infectious disease expert at Tufts Children’s Hospital said Thursday at a public meeting of an advisory panel to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. “The pattern of disease is very different in children, and lumping them in with adults would cause me some discomfort.”

But Dr. Barbara Pahud, director of research in the infectious diseases department at Children’s Mercy Hospital in Kansas City, Missouri, said it’s immoral not to get kids into trials as soon as possible.

“We should not allow children to die,” she said. “That’s our job as pediatricians to make noise and make sure people are noticing.”

COVID-19 contagion

Although most children recover well from COVID-19, they can pass the virus to their parents, teachers and grandparents, so it’s important to get them vaccinated, said Dr. Robert Frenck Jr., director of the Vaccine Research Center at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Last week, Frenck dosed his first minor with the Pfizer vaccine, and Thursday marked the first younger volunteer.

At least 500,000 American children have contracted COVID-19 this year, Frenck said, and probably a lot more. “We’re not necessarily identifying all the times when the younger ones are transmitting to parents and grandparents,” he said.

Less than 1% of those children ended up hospitalized, Meissner said, so any vaccine given to children has to meet a high bar for safety to outweigh any risks.

“I worry that the vaccines … in genetically predisposed children may elicit a very troublesome reaction,” said Meissner, a member of the FDA advisory panel that met for eight hours Thursday to discuss COVID-19 vaccine development.

But Pahud noted more than 100 children – many who were previously healthy – have died from COVID-19. That’s nearly as many as died in the last year from the flu, which saw a particularly deadly year. Others have developed a dangerous immune overreaction.

Pahud said COVID-19 is as dangerous for children as other illnesses they are vaccinated against, not counting the risk infectious children present to adults. After the pneumococcal vaccine was introduced in children, for example, doctors were pleasantly surprised to see rates of pneumonia fall.

With COVID-19, she said, “we might have more impact in herd immunity and transmission than we know.”

Another reason to test children, Pahud said: once a vaccine is approved for adults, some parents will have their children get it, even without federal approval. Absent a trial in children, there’s no way to know if that will be safe, she said, adding that she wishes such studies had started long ago. “We’re severely behind,” she said.

Vaccine testing will take longer in kids

Vaccination has focused on adults so far, in part because they are more likely to suffer ill effects from the virus, but also because that’s how vaccines are usually rolled out. Even vaccines aimed at babies are tested first in adults to make sure they’re safe, Frenck said.

While adolescents are generally given an adult dose of a vaccine, Frenck said younger children may need a lower dose, which needs to be worked out during clinical trials.

Pfizer hasn’t released any details of its roll out other than to say it plans to assess success with one age group before moving down to the next.

Frenck said he’s seen very few side effects so far from the vaccine developed by Pfizer and German company BioNTech. Most recipients are convinced they got the placebo, as half the trial participants will, because they have so few side effects, he said.

Some people experienced fatigue, muscle or joint aches or a fever for a day or two, but nothing serious enough to stop participants from going to work. “Based on all that safety data, I’m not concerned about moving into adolescents,” Frenck said. “I think their immune system and their size is basically going to see the same results.”

It’s urgent to start clinical trials in children, he added. “With something that has turned our world upside down, it gives you even a stronger reason of why you want to test now,” he said.

Pfizer has not released a timeframe for the study of adolescents, but Pahud said testing in teens and kids will take longer than in adults, because of parents’ hesitancy to expose their children to unproven vaccines.

Children who are Black or Latino, like their parents, are more likely to suffer the worst effects of COVID-19, Pahud said, so they should be prioritized in any vaccination effort. “It’s a population we need to pay attention to,” she said.

Personal perspective

Katelyn Evans, 16, decided to volunteer for the vaccine trial because she wanted to be part of the solution. “The more people they have and the more data they have, the sooner they can help people,” she said.

Last week when she got her shot, Katelyn closed her eyes as the needle went in, but said it didn’t really hurt, and she hasn’t had any side effects since.

During the pandemic, Katelyn, a high school junior, has been able to continue with her coursework, though her school switches every week or so from everyone in person to half the students coming two days a week and half the other two.

But COVID-19 has robbed the active teen from drama club, mock trial, math club, choir – where she proudly sings alto – and running cross country.

The sooner there’s a vaccine, the sooner life can get back to normal, Katelyn said, adding that she’s hoping to convince her cousin and some friends her age to join in the trial. “They need hundreds more people to get the data they need.”

Pahud said her own 12-year-old daughter asked several months ago why she couldn’t get vaccinated. “That’s not fair,” she said when Pahud told her children weren’t yet included in trials.

Pahud said she’s also hearing a lot of fear from parents worried their child will have one of the rare, bad cases of COVID-19. If nothing else, Pahud said, a vaccine should be able to stem some of that fear.

And if teachers are no longer afraid of being infected by their students, they should be more willing to reopen schools, which will help all kids and families, regardless of their COVID-19 status.

“We’re never going to get back to normal without having a vaccine available for children,” she said.

Contact Karen Weintraub at kweintraub@usatoday.com

Health and patient safety coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from the Masimo Foundation for Ethics, Innovation and Competition in Healthcare. The Masimo Foundation does not provide editorial input.