For the way-too-young-to-vote crowd, 2020 events are still a draw.

IOWA CITY — Oliver Hanlon was beaming ear-to-ear as he stood next to Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts on a riverside stage at the University of Iowa.

“I met the president,” he shouted, bounding down the steps two at a time.

His mother gently corrected him: “Not yet,” she said, while the Warren photo line snaked on behind her. Oliver couldn’t be faulted for his civics proficiency; he’s 7 years old.

The 2020 Democratic presidential campaign stops are crawling with children, some of whom spend most of the stump speeches crawling away from their parents. While all of the candidates seek to portray a family-friendly image, it takes work to bring a youngster to a campaign event: They often start late and run well into the evening, with a policy discussion not exactly accessible on the elementary-school level; bigger rallies often take place outdoors, regardless of weather.

Kissing babies and tousling children’s hair has long been a staple of retail campaigning, but in 2020 it is about more than a photo op, even the cutest of photo ops. In a historically crowded field, in an era of uncertain polling, these campaign stops are something of a past-their-bedtimes straw poll, revealing which candidates young parents deem viable or famous enough to risk a tantrum or a sleep-deprived meltdown over the next morning.

For now, the leaders appear to be Ms. Warren and former Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr., who have both taken steps to cater to the children and parents who come see them. It’s one more subtle measure of their stature in a race that is steadily narrowing from the largest primary field in history to just a handful of viable contenders.

Ms. Warren and Mr. Biden, whose staffs both go to great lengths to present their events as family friendly, are currently atop the Democratic polls, which might explain the pep talk parents often give their children before meeting the two candidates: You are talking to the next president.

Ms. Warren lets families with children cut to the front of her selfie line, a strong incentive given that supporters often wait hours for a 20-second interaction and photograph. Mr. Biden’s campaign stops over the summer and fall have often come with free ice cream — and if frozen dairy products are not available, he’s been known to hand out cash with instructions for children to tell their parents to stop for a treat on the way home.

During a Labor Day swing through Iowa, Mr. Biden worked a chocolate-and-vanilla swirl machine at one union picnic and handed out ice cream sandwiches at another.

Last month in Iowa City, Clara Engler, 5, spent hours before an evening Warren rally at the University of Iowa practicing the “pinkie promise” that has become a staple for young girls at Ms. Warren’s events. With her mother, Brooke Engler, an Iowa City cosmetologist, Clara worked on locking fingers briefly and looking up, so she could hear Ms. Warren tell her that running for president is “what girls do.”

When the moment came, about a half-hour after Clara’s bedtime, Ms. Warren got down on one knee, looked her in the eye and made the promise. Clara jumped up with glee. Her mother beamed.

“She’d seen it before on TV,” Ms. Engler said. “It’s nice that I can have my child sit back and watch politics without worrying about what will be said.”

The others in the 19-candidate Democratic field aren’t overtly inhospitable to children, but former Representative Beto O’Rourke of Texas peppers his stump speech with profanity and Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont isn’t a fuzzy figure while delivering his policy-heavy stemwinders. In early September he scolded a crying baby to “keep it down” during a campaign stop in New Hampshire.

Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Ind., whose most fervent supporters tend to be young enough not to have children of their own, often attracts older kids — particularly L.G.B.T. teens inspired by the first openly gay major candidate for president.

“When you know that there’s something historic about your campaign, you feel a level of responsibility that goes with that,” Mr. Buttigieg said aboard his Iowa campaign bus last month. “It certainly adds a level of motivation when people come up to you, sometimes with tears in their eyes, just letting you know what the fact of your campaign means to them.”

Even in Iowa, where rare is the weekend without a presidential hopeful stumping nearby, it takes a serious commitment and coordination to attend a campaign event with young children.

“If she starts crying we’ll run out quickly,” Elizabeth Batey, a lawyer from Waverly, Iowa, said of her 2-year-old daughter, Hattie, while waiting for Mr. Buttigieg last month in a stuffy storefront in Iowa Falls.

Ms. Batey, whose 4-month-old son, George, was asleep in his car seat, made it through Mr. Buttigieg’s event without having to flee. Afterward, she waited on the sidewalk in front of the Buttigieg campaign bus, holding one child in each arm.

“Wow, you’ve got your hands full,” Mr. Buttigieg told her before pausing for a picture.

Parents interviewed at a range of campaign events said they often felt like this political moment resembled a tawdry reality TV show, and they brought their children to see the 2020 candidates to try to demonstrate to them that politics can be something different.

“I can’t let my kids listen to the TV without being ready to hit the mute button,” said Julia Privett, a physician assistant who brought her 2-year-old daughter, Alyssa, to see Mr. Biden talk about climate change in Cedar Rapids.

Lytishya Borglum, a Cedar Falls small business owner, brought her three middle-school-aged children to see Senator Kamala Harris of California speak at the University of Northern Iowa. She’d taken her oldest daughter, 13-year-old Berlyn, to see Democratic caucus campaign events in 2008, but skipped 2016 because it was too toxic.

“Nowadays, it’s impossible for them not to be exposed to the craziness in the White House,” Ms. Borglum said.

At Ms. Warren’s Iowa City rally, a parade of children waited with their parents for a picture with the senator. Kohner Reynolds, who will turn 2 in November, blew past his 7:30 p.m. bedtime.

“He fell asleep a couple times in the baby carrier,” said Kohner’s mother, Callie Reynolds. “I wanted him to be able to say he came to see her.”

Burgundy Johnson, a child psychologist, kept her 5-month-old son, Archer, up past his 8 o’clock bedtime. She occupied Archer with toys.

“I wanted a picture of Elizabeth Warren holding my baby,” she said while leaving the event at 8:40 p.m. “Now it’s going to be an interesting night.”

The older children tend to be more attuned to issues.

Evelynn Parlet, 11, an Iowa City sixth grader, said she approved of Ms. Warren’s campaign goal of reordering the American economy.

“I liked what she said,” she said. “We need to help people who don’t have enough money.”

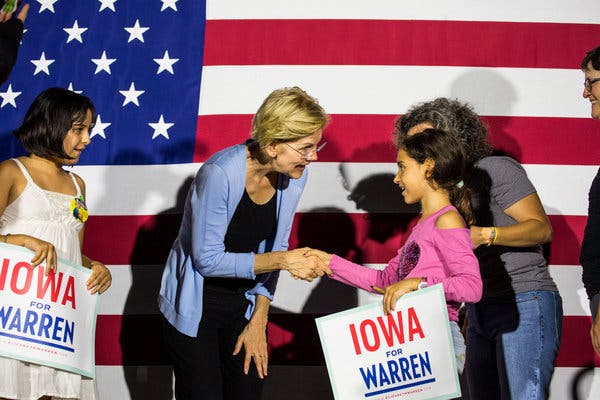

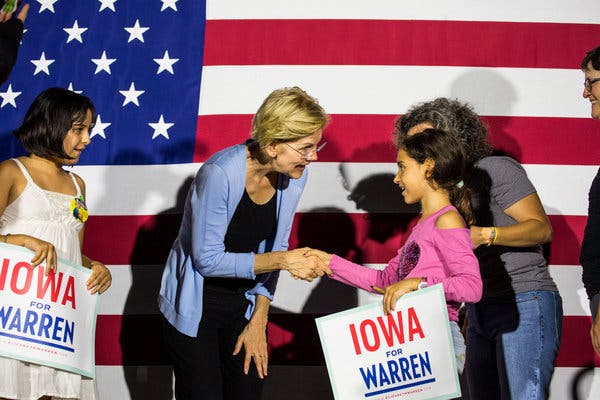

Samara and Isa Murillo, sisters who are 10 and 8 years old, each had Ms. Warren autograph a white campaign placard. Ms. Warren got down on one knee and signed them on the floor of the stage.

“We love her ideas about change and the two cents,” Samara said. “People out there are dying of hunger.”

Isa said she was more focused on climate change. “Some people don’t have homes because of the flooding,” she said.

And, because it is Iowa, there are parents who spend caucus season vying to get their children photographed with all of the candidates they can — just in case one of them makes it to the White House.

Eric Heininger, a fund-raiser for nonprofit organizations, and his wife, Tiffani Milless, a physician, toted their 9-month-old daughter, Charlotte, around the Polk County Steak Fry last month to get her in pictures with as many contenders as possible. Dressed in a red-white-and-blue sundress, Charlotte met Ms. Warren, Mr. Buttigieg, Mr. O’Rourke and the entrepreneur Andrew Yang. At earlier campaign events, she was photographed with Mr. Sanders, Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey and former Gov. John Hickenlooper of Colorado, who ended his campaign in August.

With Charlotte sleeping on her father’s chest, Dr. Milless filled out a card committing to caucus for Mr. O’Rourke and held it up while the Texan offered his toothy smile.

“Thank you so much,” Mr. O’Rourke said, gently patting the sleeping child on her back. A campaign aide took Dr. Milless’s caucus card and stuffed it into a backpack.

Afterward, Dr. Milless said she had only filled out the card in order to secure the picture with her daughter.

“He’s in my top three,” she said. “It’s a loose commitment, kind of like a promise ring.”

A version of this article appears in print on , Section A, Page 19 of the New York edition with the headline: Past a 7-Year-Old’s Bedtime? Not When These Candidates Are in Town. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe